Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, born in Paris in 1947, is a French virologist. From 1992 - 2015 she was the Director of the Regulation of Retroviral Infections Unit at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. In 2008, together with Luc Montagnier, she was awarded the Nobel Prize of medicine for the discovery of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 1983.

Over the last three decades, she has been continuously working on HIV/AIDS research and strongly involved in promoting integration between HIV/AIDS research and interventions in resource limited countries. She has always been committed to fighting for the rights of patients and against the spread of the AIDS disease.

In 1966 she entered the University of Paris to study life sciences. During her studies, she was eager to gain laboratory experience. She was recruited as a volunteer in Jean-Claude Chermann who was studying the relationship between retroviruses and cancers in mice at the Institut Pasteur. He proposed to her a PhD project to study the antiretroviral activity of a synthetic molecule (HPA23) in leukaemia induced by Friend virus in mice. Tests proved effective and Barré-Sinoussi was awarded her PhD in 1974.

She then spent a year on a post-doctoral project at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health in the US before returning to France to take up the offer of a research position in Chermann’s laboratory in Paris working in the department led, at the time, by Professor Luc Montagnier. This research group was one of the few which continued to study the link between retroviruses and cancers, as by this time oncogenes were attracting more attention.

In the early 80’s, as the first cases of AIDS started to appear throughout the world, including France, the Institut Pasteur team was approached by a group of French clinicians to investigate whether this new disease could be caused by a retrovirus. It was Barré-Sinoussi who first observed evidence of reverse transcriptase activity in a lymphocyte culture derived from a patient lymph node biopsy. The retrovirus the team had discovered was later named human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

After visiting Africa as part of a World Health Organisation workshop in 1985, Barré-Sinoussi determined to champion her scientific cause on a global scale, starting collaborative efforts and scientific exchanges with African and Asian countries.

Barré-Sinoussi retired from the Institut Pasteur in 2015 but remains Honorary President of the International Network and of the Virology Department of the Institut Pasteur and member or chair of many international scientific advisory panels and boards. Her former collaborators are continuing the work towards better comprehension of AIDS pathogenesis and mechanisms of control of HIV/AIDS at the Institut Pasteur and elsewhere. She is author and co-author of more than 300 original publications and of more than 125 review articles.

In 2009, Barré-Sinoussi was elected member of the French National Academy of Science and of the American National Academy of Medicine in 2018. She has been President of the International AIDS Society (IAS) between 2012 and 2014. In 2016, she has been elevated at the rank of Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor in France.

Exhibition "Sketches of Science" by Volker Steger - Locations & Dates

By Volker Steger

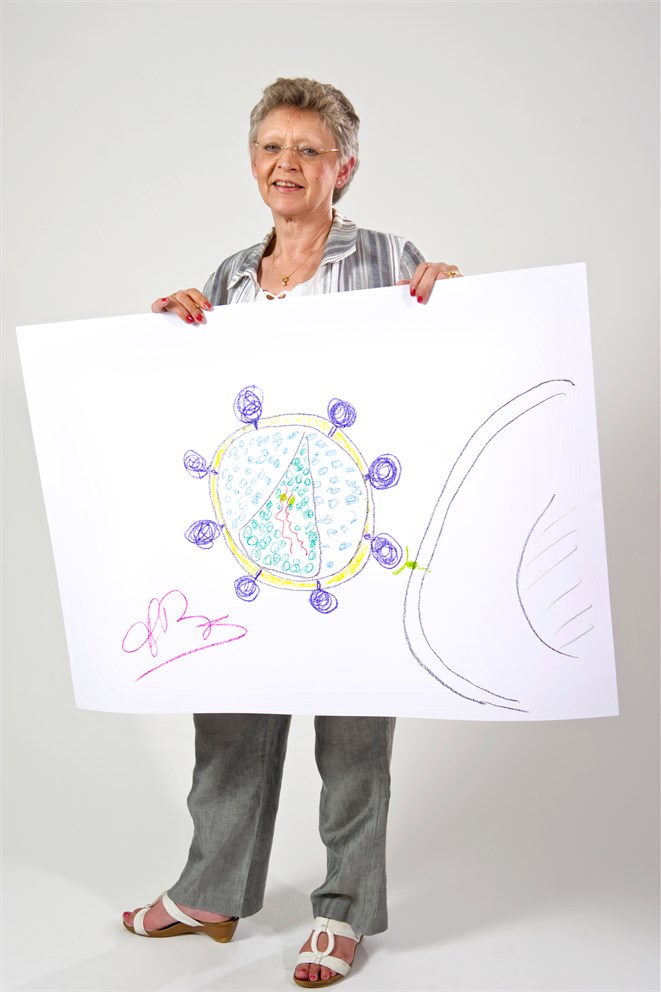

Francoise Barré-Sinoussi draws an AIDS virus and smiles.

I remark that Luc Montagnier, who shares the Nobel Prize

with her for discovering the virus, said that one should not smile

when dealing with something as serious as AIDS.

Barré-Sinoussi smiles even more broadly and says:

“One cannot not-smile for 25 years!”

Francoise Barré-Sinoussi zeichnet ein AIDS-Virus und lächelt. Ich

erinnere sie daran, dass Luc Montagnier, mit dem sie sich den

Nobelpreis für die Entdeckung des Virus geteilt hat,

einmal äußerte, dass man nicht lächeln sollte,

wenn man mit so etwas Ernstem wie AIDS zu tun hat.

Barré-Sinoussi grinst noch breiter und sagt:

„Man kann nicht 25 Jahre lang nicht-lächeln!“

Picturing the Enemy

by Adam Smith

This is a portrait of an invasion. The colourful centrepiece is HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, which Francoise Barré-Sinoussi and her colleague Luc Montaigner first identified in the mid-1980s, just two years after the first cases of AIDS had come to light. But a virus needs a host to survive and flourish, and this virus particle is here depicted in the process of attaching itself to a small green receptor on a white blood cell. This is the start of the process by which the virus will integrate its own genetic material into the genome of the infected cell, with all the terrible consquences that humankind has been made so tragically aware of over the last three decades or so.

The virus anchors itself to the receptor on the host cell by means of an envelope protein, here depicted as a purple circle rooted in the yellow membrane that surrounds the virus particle. The cone-shaped core of the virus, containing the apparatus for the invasion, is shown as a triangle, looking a little like a slice of pizza. Within this core lies the genetic material of the virus, those thin red, wiggly lines representing the RNA. HIV is a retrovirus, relatively unusual among the types ofvirus that infect humans, and uses the host cell’s own machinery to manufacture new viral DNA. Sitting at the top of the RNA strands are seen two light green blobs, indicating the enzyme, reverse transcriptase, that will catalyse the conversion of the HIV particle’s RNA into DNA.

The triangle contains other molecules important for the virus’ multiplication, but reverse transcriptase was the target of the first drugs developed to inhibit HIV’s spread and so here it is given prominence. These days there are happily drugs on the market acting at a variety of different points in HIV’s life cycle, including that critical attachment point with the cell surface receptor shown here. As Barré-Sinoussi points out, used in combinaton, these drugs can now reduce mortality by 90%, and early treatment can also hinder the transmission of the virus from person to person, thus preventing, as well as treating, AIDS. “It’s wonderful progress”, Barré-Sinoussi admits, but goes on to caution that “Only 40% that need to be treated are on treatment in the developing world… we can do better.”