Sheldon Glashow shared the 1979 physics award with Harvard colleague Steven Weinberg and Pakistani-born physicist Abdus Salam (1926–96), for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles. The discovery of radioactivity and the development of nuclear physics led to the concept of nuclear forces. The strong force keeps protons and neutrons together in the nucleus, the weak force causes the so-called radioactive beta-decay.

It is the weak force that starts the first of the chain reactions that causes the sun to burn. It also governs radioactive elements in medicine and technology, and is the basis for the carbon-14 dating method. A low energy theory of weak interaction was first put forward in 1934 by Enrico Fermi. All fundamental forces operate by the interchange of subatomic particles. The electromagnetic force, e.g., is mediated by photons. In the 1960s Glashow, Salam and Weinberg each linked the weak nuclear force and the electromagnetic force together as manifestations of a unified electroweak force. Glashow also found a way to extend their theory to other classes of elementary particles. In doing so, he invented a new property of quarks which he called ‘charm’.

Glashow’s Jewish parents moved to New York from Russia in the early 1900s. Sheldon was an ‘afterthought’, born in 1932 when his brothers were in their teens, and they helped him set up a basement chemistry lab when he was 15. He attended the Bronx High School of Science where he first met Steven Weinberg, and both ended up at Cornell University, where he gained a BA in 1954. At Harvard, under Julian Schwinger, Glashow’s thesis showed an early interest in electroweak synthesis. The duo even began to write a paper on weak-electromagnetic unification but the first draft was lost.

Glashow received his PhD in 1959 and won an NSF postdoctoral fellowship, to work in Moscow with Igor Tamm, but only got as far as the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen and CERN in Geneva. The Russian visa never came. During that time, however, Glashow put forward his theory on the electroweak structure and was ‘discovered’ by Murray Gell-Mann, who invited him to Caltech as a research fellow in 1960. The Following year Glashow joined Stanford University as assistant professor, then moved to UC Berkeley as associate professor and in 1966 returned to Harvard as professor, rising to Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics. In 1969, with John Iliopoulos and Luciano Maiani, Glashow predicted the existence of charmed hadrons (quarks), and in 1974 he predicted that charm would be discovered in neutrino physics.

Glashow left Harvard in 1982 and joined the University of Houston, Texas, as Affiliated Senior Scientist. In 1984 he also joined Boston University as Distinguished Visiting Scientist. Glashow is Eugene Higgins Professor Emeritus at Harvard and the Arthur G.B. Metcalf Professor Emeritus of Mathematics and the Sciences at Boston University.

In 1972 he married Joan Alexander. They have four children.

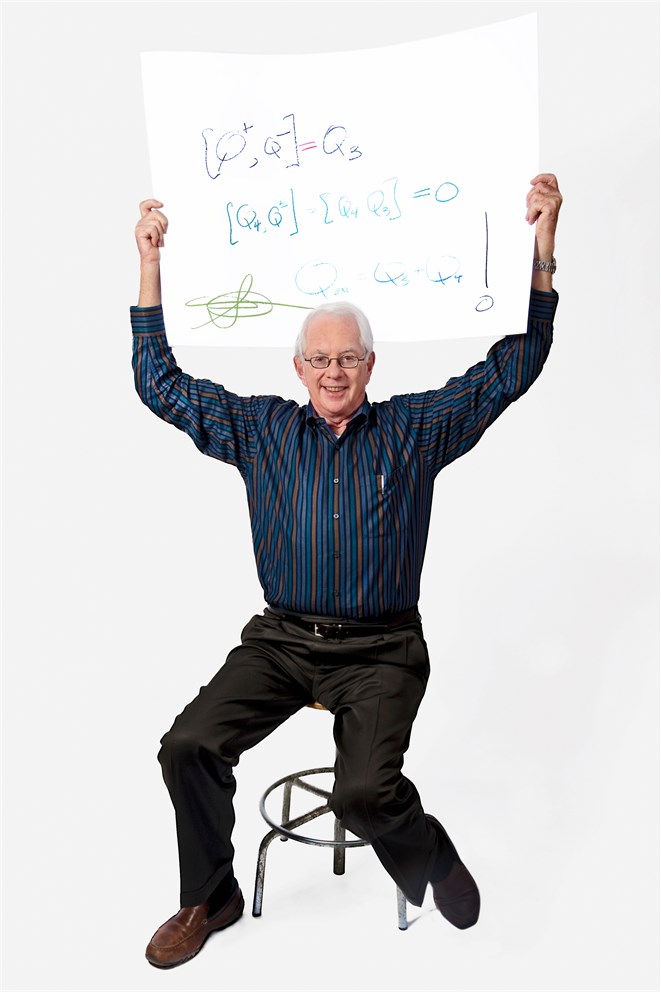

This text and the picture of the Nobel Laureate were taken from the book: "NOBELS. Nobel Laureates photographed by Peter Badge" (WILEY-VCH, 2008).

Exhibition "Sketches of Science" by Volker Steger - Locations & Dates

By Volker Steger

Did he have some kind of electroweak interaction somewhere along

the way or did he just meet a charmed quark? Anyway, I have to

wait a little while for Sheldon Glashow, who is very much in demand

on this day at CERN. After making his sketch, he asks for a chair for

the photo session. Just any kind of stool – a standard model.

Hat er irgendwo unterwegs eine Art elektroschwache

Wechselwirkung oder ein Charme-Quark getroff en? Egal, ich

jedenfalls muss auf Sheldon Glashow warten, der an diesem Tag

beim CERN sehr gefragt ist. Nachdem er seine Zeichnung angefertigt

hat, bittet er um einen Stuhl für das Fotoshooting.

Irgendeine Art von Stuhl – ein Standardmodell.

No Simple Explanation

by Adam Smith

“Clearly I could not think of anything pictorial,” recalls Sheldon Glashow. “Nor, I imagine, could James Clerk Maxwell have thought of some interesting, curious picture to write down when he wrote down his Maxwell equations, or Einstein when he wrote down the general theory of relativity, say.” Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979 for their contibutions to the understanding of the weak interaction. The weak interaction, or force, is one of the four fundamental forces of nature and is responsible for the radioactive decay of subatomic particles. Glashow in particular developed an algebraic formulation of an electroweak model that combines the weak interactions with electromagnetism, another of the fundamental forces. Referring to his sketch, Glashow remarks that “actually these formulas have a significance to me of having to do with quite a lot of work even well beyond what I shared the Nobel Prize for.”

He goes on to talk about the problems of communicating science to a general audience; “It’s very hard to talk about quantum mechanics or relativity when there’s no background of anything having to with the nature of research or the understanding of the laws of physics. Where do you start? What I’ve written down is commutation relations. The commutator of Q+ with Q- is Q3. You may or may not want to explain what a commutator is. It’s [Q+, Q-] – [Q-, Q+] for example. And then in the other ones, [Q4, Q+] – [Q+, Q4] is equal to zero, etc. Okay, so it’s a bunch of commutators, algebraic things, and then with an exclamation point, the electric charge, which is QEM is Q3 + Q4. Obviously somebody is excited about that.”

Thinking about other pictures that he sometimes uses to engage public audiences, Glashow suggests that “Another picture that I’ve used on many occasions is Ouroboros, the snake that swallows its own tail, because that has a great deal to do with the synthesis between the large and the small. The fact that particle physics is not just the study of the smallest things in the world but it’s also a key to understanding the structure of the universe as a whole, and there’s been an enormously successful and productive convergence between cosmology on the one hand and particle physics on the other. Something that actually started a long, long time ago.”