Biochemists have been keen to explore how proteins are created in all living things, but for years seemed less interested in what happened to the excess. Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover and Irwin Rose examined the problem of how cells break down unwanted proteins, and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

Hershko was born Ferenc Herskó in Karcag, Hungary, on the last day of 1937. During WWII, his father was taken as a forced labourer to the Russian front, where he was captured by the Russians and released only in 1946. The rest of the family served as labourers in Austria. When they were reunited they lived in Budapest until emigrating to Israel in 1950. Settling in Jerusalem, Avram fared well in all subjects at school, and in 1956 followed his brother’s example and entered the Hebrew University – Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem, where he “fell in love” with biochemistry, inspired by good teachers including Jacob Mager. Hershko joined Mager’s laboratory in 1960 and worked on several projects, finished his medical studies, did military service as a physician (1965–67) and then returned to finish his PhD. He spent 1969–71 as a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics of the University of California in San Francisco.

On his return to Israel, Hershko was offered the role of Chairman of Biochemistry at the new Technion medical school in Haifa. It was there that much of the groundwork for the Nobel discovery was made, with assistants including his biologist wife Judith (they met and married in 1963 and have three sons and several grandchildren). In 1977, Aaron Ciechanover joined the team. Hershko spent a sabbatical year in Philadelphia, working with enzyme specialist Irwin ‘Ernie’ Rose who was also interested in protein degradation. Rose suggested (and Ciechanover insisted) Hershko apply for a research grant from the US National Institutes of Health, and in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Hershko, Ciechanover and Rose worked together at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

They discovered that cells destroy redundant proteins in a phased process. A molecule called ubiquitin (“because it occurs everywhere”) attaches to a target protein and accompanies it to a proteasome – a sac of powerful enzymes that break the protein into its component amino acids. Only proteins carrying a ubiquitin molecule are admitted, and the ubiquitin detaches itself to be reused. Their work explained how the cell controls processes such as cell division, DNA repair and the immune system by only breaking down certain proteins. Diseases such as cystic fibrosis and cervical cancer result when protein-degradation does not work normally and knowledge of the process may help develop drugs against these diseases.

Exhibition "Sketches of Science" by Volker Steger - Locations & Dates

By Volker Steger

A quiet and soft-spoken man enters the studio. He sits down and starts

to sketch. Itʼs only when I ask to photograph him that I know what has

characterized him all along: His warm smile.

An educator. And benchwork, he says, is his hobby!

Ein ruhiger und zurückhaltender Mann betritt das Studio. Er setzt sich und

beginnt zu zeichnen. Erst, als ich frage, ob ich ihn fotografi eren darf, weiß

ich, was ihn auf ganzer Linie kennzeichnet: Sein warmherziges Lächeln.

Ein Pädagoge. Und an der Werkbank arbeiten, sagt er, ist sein Hobby!

Targeted for Elimination

by Adam Smith

The second half of the twentieth century saw a great deal of attention paid to the question of how proteins get made. And while vast numbers of researchers strived to understand protein synthesis, the way in which the genetic code gets translated into the proteins that make up living organisms, almost no-one gave any thought to how proteins get eliminated. Either people weren’t aware that this happened, or if they were aware they thought it unimportant. Some people even said it couldn’t happen, as in the famous case of the great biologist Jacques Monod, whose generalization that there was no protein degradation at all was accepted for a while.

Against this tide of interest in protein construction, Avram Hershko and his co-Laureates Aaron Ciechanover and Irwin Rose chose to study protein destruction. They discovered that in order for a protein to get degraded it first has to be linked to another protein, called ubiquitin. This is the tagging process for degradation and by revealing this mechanism the three researchers solved the big mystery of how the cell ‘knows’ which protein to degrade at which time.

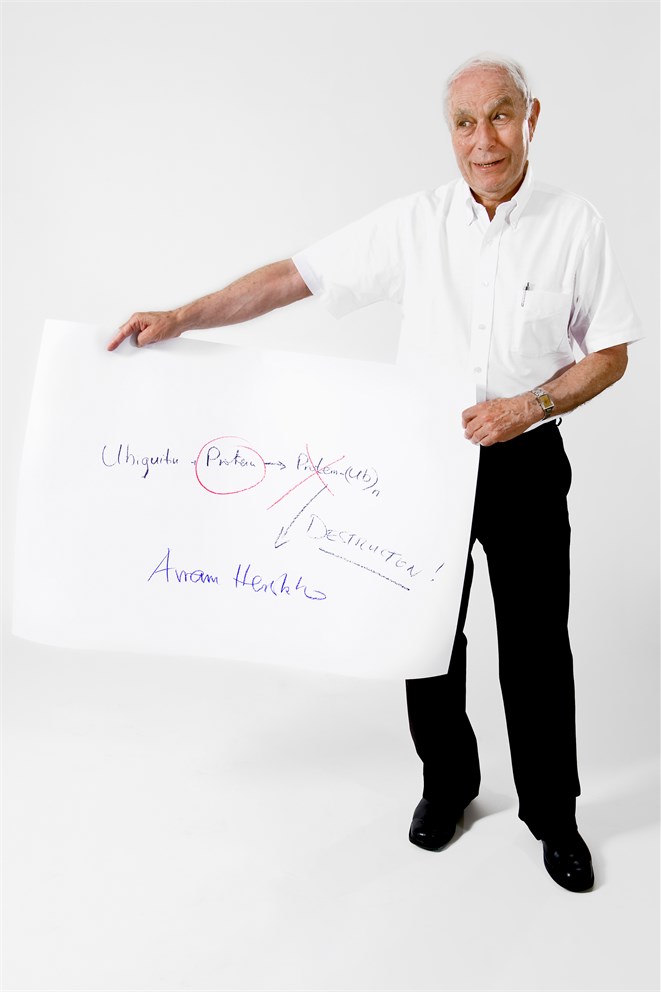

Hershko’s simple reaction scheme shows the progress of such a labelling event, with a protein linking to an unspecified number of ubiquitin molecules, giving rise to a tail of ubiquitins signified by (Ub)n. The cell’s degradation machinery then recognises the ‘polyubiquitin’ chain as the signal to act, and the protein is directed to be disassembled in the cell’s own waste disposal system, known as the proteasome. This is an extremely selective process, allowing the cell to regulate its processes with exquisite sensitivity. When revealed, in the early 1980s, this mechanism astonished people. “At least it was astonishing to me,” says Hershko. Some people didn’t believe it, but now ubiquitin-mediated degradation of proteins is know to be a fundamental process lying at the heart of both health and disease.

As for the simplicity of the drawing, “I tend to be concise,” says Hershko. “Yeah, usually I write short letters. Maybe that is reflected in the scheme, that I tried to write the main things, but in a very short way.”