Most of us take the materials around us for granted, but to a physicist, each substance is a challenge, containing trillions of atoms that interact with each other in complex ways. The problem is how to identify simple principles by which we can understand the material and predict new behavioural traits and phenomena.

The 2016 Nobel Laureates in the field of physics – David Thouless, Duncan Haldane and Michael Kosterlitz – demonstrated how materials can be understood in terms of the mathematical principles of topology, a modern form of geometry that studies different sorts of spaces. A topological surface is partly defined by how many holes there are. In topological terms, a doughnut and a cup are the same (both having one hole), but a ball is different. Its importance here is that it explains why electrical conductivity inside thin layers changes in integer steps. Using topology, two of the laureates studied the properties of ultra thin films (Kosterlitz and Thouless). Their work identified new and unexpected phases of matter and new behaviors.

The work of the three laureates was a watershed in understanding and calculating the properties of material systems, and it is thought it may pave the way for a new generation of quantum computers. The Nobel Committee for Physics declared: “This year’s laureates opened the door on an unknown world where matter can assume strange states. They have used advanced mathematical methods to study unusual phases, or states, of matter, such as superconductors, superfluids or thin magnetic films. Thanks to their pioneering work, the hunt is now on for new and exotic phases of matter.”

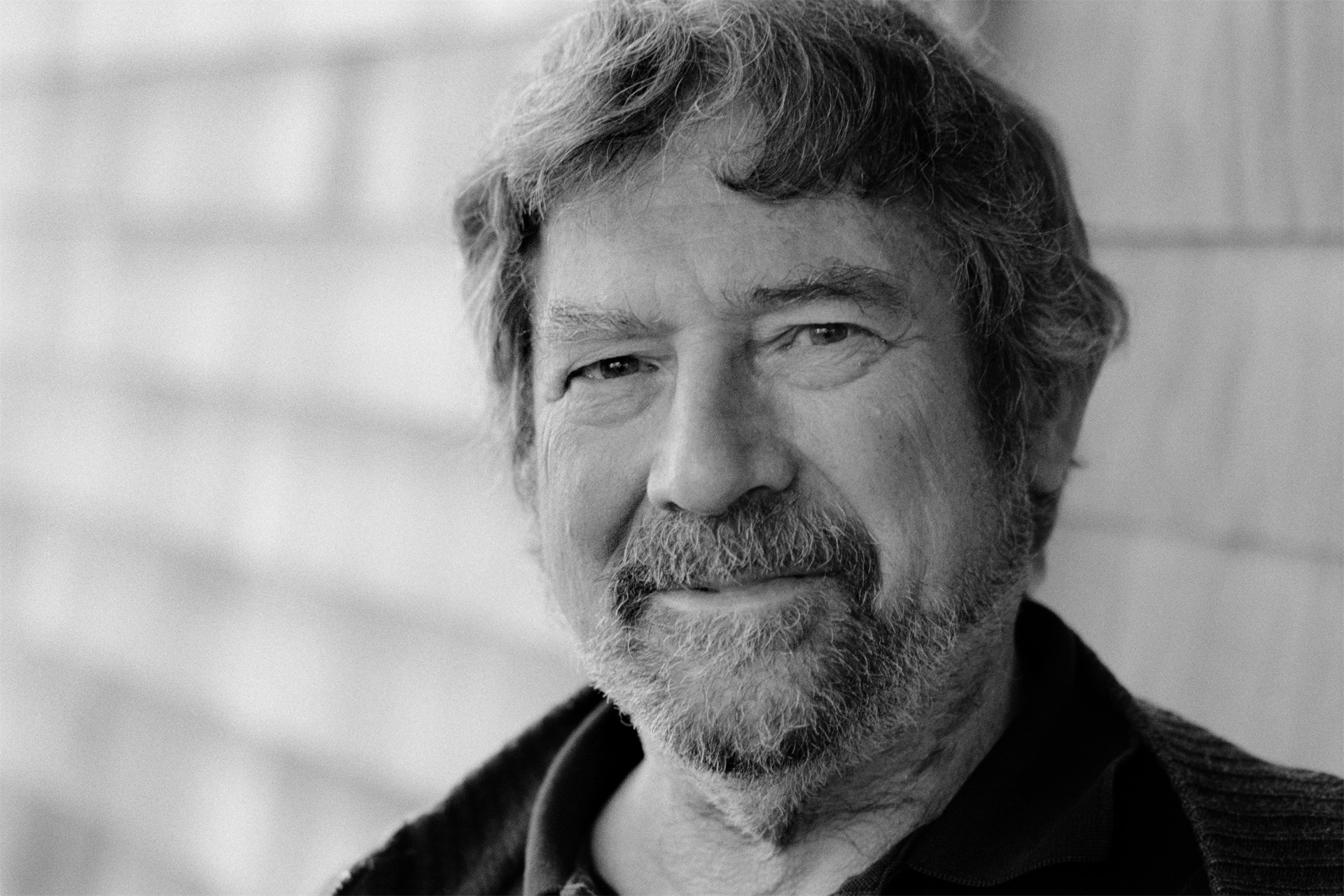

John Michael Kosterlitz was born in June 1943 in Aberdeen, Scotland, to German parents. His father, biochemist Hans Kosterlitz, took his family and fiancée Hanna Gresshöner to Scotland where he worked at the University of Aberdeen after losing his job at a Berlin teaching hospital under the Nazi regime in 1934.

Kosterlitz studied at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, earning his BA and MA before moving to Brasenose College, Oxford, where he gained his DPhil in 1969. He performed post-doctoral work with David Thouless at the University of Birmingham and, building on work by Russian physicist Vadim Berezinskii (1935-1980), they discovered the Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless phase transition of two-dimensional models at low temperature.

Kosterlitz also worked at Cornell University, New York, before being appointed as lecturer, senior lecturer and reader at Birmingham in 1974. In 1982 he moved to the US as professor of physics at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. In 2016 he also worked as visiting research fellow at Aalto University, Finland, as visiting professor at Suzhou University in China and as distinguished professor at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study.

Apart from the Nobel Prize, Kosterlitz was awarded the Maxwell Medal and Prize by the British Institute of Physics in 1981 and the Lars Onsager Prize from the American Physical Society in 2000. He is also a Fellow of the American Physical Society, Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and elected in 2017 to the National Academy of Sciences. He is married and has three children, one son and two daughters.