One fundamental question that has intrigued mankind with every night sky is: are we alone? With myriad stars to contemplate it seems unlikely, but first we have to find another Earth. The first step in that quest – the discovery of a planet outside our solar system orbiting a solar-type star – earned Michel Mayor and his student colleague Didier Queloz a quarter share each of the 2019 Physics Prize. The other half went to Canadian James Peebles for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology.

The two Swiss scientists made their discovery using custom-made instruments at the Haute-Provence Observatory in southern France in 1995. The planet - 51 Pegasi b - is hardly habitable, being a gas giant similar to Jupiter, but was the first confirmed recording and opened the floodgates. To date, more than 4,000 planets of various types have been spotted in our galaxy, the Milky Way, in more than 3,000 ‘solar’ systems.

51 Pegasi b, so named because it orbits the star 51 Pegasi about 50 light years from Earth, was also an eye-opener for astronomers, as it is far closer to its sun than expected – only eight million kilometres away, it has a surface temperature of more than 1,000°C and completes its orbit in just four days. Previously it was thought planets of this size had to exist further out – Jupiter, for example, takes almost 12 years to orbit the Sun. These discoveries have led to new theories about the creation of planets.

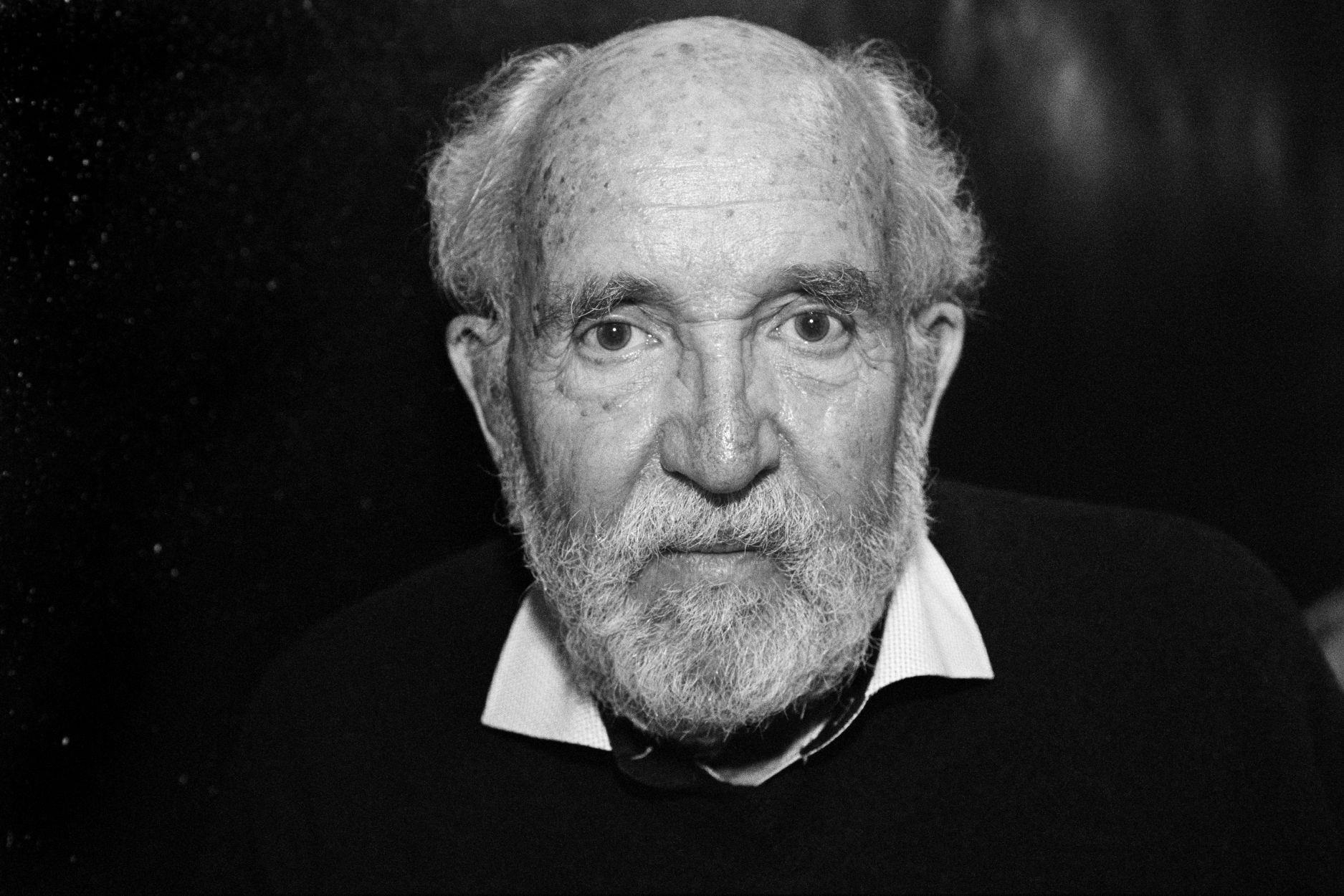

Michel Gustave Édouard Mayor was born in Lausanne, Switzerland, in January 1942. The young Michel loves the sciences, saying he was inspired by his biology teacher at his college in Aigle. He attended Lausanne University, where he gained his master’s degree in physics in 1966, before moving to the nearby University of Geneva where the decision whether to pursue solid state or astrophysics was decided over drinks with a fellow student and because, he says, he always liked looking at the stars on scout camping trips. Thus fated, he received his PhD in astronomy for his thesis on the spiral structure of galaxies in 1971 and promptly joined the faculty, rising to professor in 1988, being named director of the Geneva Observatory in 1998 and retiring in 2007 but continuing his work as professor emeritus and researcher. He is married to Françoise.

Detecting distant planets takes more than a telescope. In the 1970s, Mayor and Antoine Duquennoy at Geneva Observatory began a survey, looking for double stars. To obtain better data, they teamed up with André Baranne at the Marseille Observatory to develop the CORAVEL spectrometer, which provided accurate measurement of star movements, including their rotational speed, and was installed at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence in 1977. In the 1990s the team was joined by doctoral student Didier Queloz, who helped develop an even more accurate device known as ELODIE. Installed in 1994 ELODIE could detect a Doppler-shift ‘wobble’ in distant stars, showing the influence of the gravitational pull of an orbiting object. This data, especially when combined with ‘transit photometry’, measuring the dip in light from a star as objects pass in front of it, can be used to calculate the size, mass, distance and speed of the orbiting object.