Mario José Molina is a Mexican-born chemist who was jointly awarded the 1995 chemistry prize, along with F. Sherwood Rowland (US) and Paul J. Crutzen (Netherlands), “for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone.” Most people are aware of the threat to the ozone layer, which shields the Earth from solar radiation, but it was as early as the 1970s that Molina and Rowland first highlighted the problem. Their work led to an international agreement to cut the use of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases.

Professor Molina was born in Mexico City, Mexico, in 1943. He holds a Chemical Engineer degree (1965) from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, a postgraduate degree (1967) from the University of Freiburg, Germany, and a Ph.D. in Physical Chemistry (1972) from the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), with a joint appointment in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Prior to joining UCSD he was an Institute Professor at MIT, and he held teaching and research positions at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the University of California, Irvine and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology.

Professor Molina has been involved in developing our scientific understanding of the chemistry of the stratospheric ozone layer and its susceptibility to human-made perturbations. He was a co-author, with F. S. Rowland, of the 1974 publication in the British magazine Nature, of their research on the threat to the ozone layer from chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases that were being used as propellants in spray cans, as refrigerants, as solvents, etc. More recently, Professor Molina has also been involved with the chemistry of air pollution of the lower atmosphere, and with science-policy issues related to the climate change problem.

Professor Molina served on the President's Committee of Advisors in Science and Technology (1994-2000; 2010-2016), and on several more advisory boards and panels. He is a member of the US National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine, the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and of the Mexican Academy of Sciences. He has received more than forty honorary degrees, as well as numerous awards for his scientific work including the Tyler Ecology and Energy Prize in 1983, the UNEP-Sasakawa Award in 1999, and the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, as well as several governmental recognitions from around the world. Prof. Molina is married to Guadalupe Álvarez and mainly resides in Mexico City.

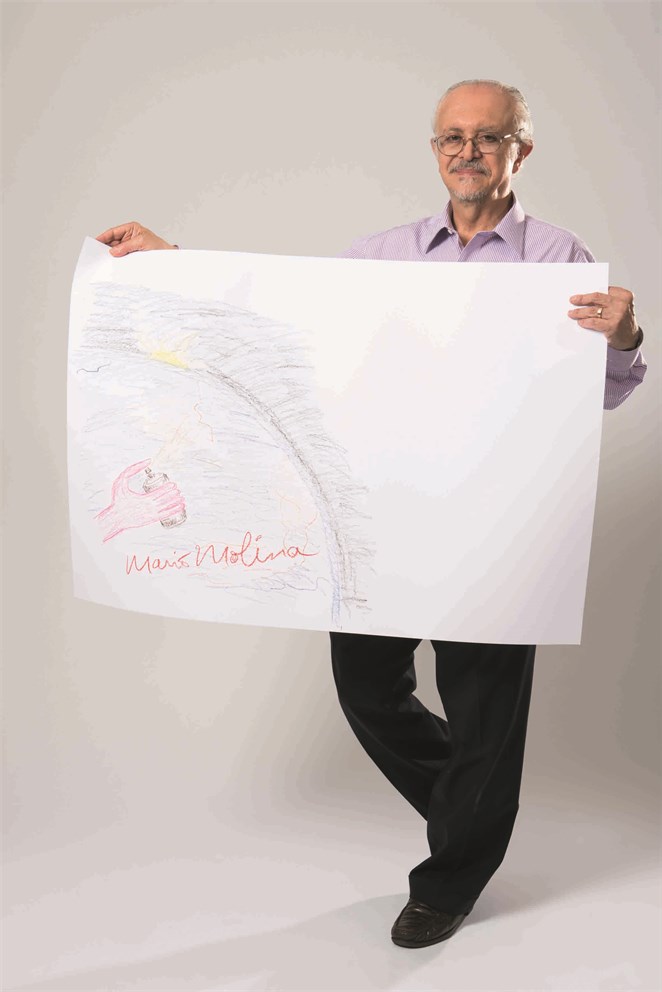

This adapted text and the picture of the Nobel Laureate were taken from the book: "NOBELS. Nobel Laureates photographed by Peter Badge" (WILEY-VCH, 2008).

Mario J. Molina passed away on 7 October 2020 at the age of 77.

Exhibition "Sketches of Science" by Volker Steger - Locations & Dates

By Volker Steger

Mario Molina took a little while to sketch “what he got his Nobel Prize

for”. But the result is so clear, that one gets the message right away:

Spray cans destroy the ozone layer that protect us from UV rays.

But things got better, new spray cans cause less harm

to the ozone layer. Thanks to Mario Molina!

Mario Molina brauchte eine Weile für die Zeichnung seiner

Nobelpreis-Entdeckung. Doch das Ergebnis überzeugt, und man

versteht die Botschaft sofort: Sprühdosen zerstören die Ozonschicht,

die uns vor UV-Strahlung schützt.

Mittlerweile sind Sprühdosen viel weniger schädlich für die Ozonschicht

– dank Mario Molina!

When Local Became Global

by Adam Smith

“It’s a representation of the fact that we can protect our planet if we understand what we are doing to it,” says Mario Molina, looking again at his sketch. Against a backdrop of planet Earth, with its atmosphere represented by grey shading, a hand presses down on a spray can. The spray can is symbolic of the industrial chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases that, in an article published in 1974, Molina and his colleague Sherwood Rowland said were damaging the protective ozone layer in the stratosphere. CFCs were ubiquitously employed as propellants in spray cans and as refrigerants, and it took time to convince people of the link between these gases and the holes that were appearing in the ozone layer. But, eventually, a CFC ban came into force. “Fortunately society did get together, our hypothesis was tested scientifically and,” Molina continues, “The main point here is that through an international agreement the problem was solved.”

Back in the 1970s, there were no precedents for the idea that local behaviour could have a truly global impact. The CFCs are extremely stable compounds, and no matter where they are released they mix with the atmosphere, encircling the planet. Indeed, the most dramatic effects on the ozone layer were seen above the Antarctic, as far away as possible from the sites of the CFC emissions themselves. That apparent separation of cause and effect was one of the reasons for people’s initial scepticism. “We realised we had to be patient and persistent and we had to learn to communicate with the public at large, not just with other scientists,” recalls Molina. “We showed that society can respond to the scientific community when our reasoning is valid.”

Notice the sunrise at the top of the picture. Now, in the face of global climate change, Molina sees the historical example of the response to CFCs as providing a model for how the world can come together to tackle the threats posed by the changing climate. “Coming back to the precedent,” he says, “It can be done in a way that the economy’s not affected, jobs are not lost. Society was able to replace CFCs, the economy did not suffer; the other way around actually, it continued to grow. So, in some senses, the sunrise is a symbol of our hope that we’ll be able to solve all these problems.”