It is possible that a perceptive science teacher in Ohio of the 1940’s may have helped save the planet. For that teacher allowed a bright, responsible pupil to look after the local volunteer weather station. And that pupil was Sherwood Rowland, who grew up to be the scientist who realised that chlorofluorocarbons contribute to ozone depletion.

Rowland was born in 1927, in Delaware, Ohio. He graduated from school early, shortly before his sixteenth birthday, and enrolled at Ohio Wesleyan University, where his father was Professor of Mathematics. He volunteered for the U.S. Navy in June 1945 and was discharged in August 1946. He returned to Ohio Wesleyan where he majored in chemistry, physics and mathematics, graduating in 1948, before going on to the University of Chicago and gaining an MSc in 1951, and PhD in 1952. At Chicago he worked as a radiochemist with Willard F. Libby, who had just developed the carbon-14 dating technique, and several leading scientists from the Manhattan project, who had been lured there by Chicago’s nuclear reactor, built by Enrico Fermi in 1942 under the football stands.

Just three weeks before his 25th birthday, in June 1952, Rowland married fellow graduate Joan Lundberg. He then took a job as Chemistry Instructor at Princeton. The couple have two children. Rowland developed a new sub-field of tritium ‘hot atom’ chemistry, which he pursued when he moved to the University of Kansas in 1956, and when, in 1964, he joined the University of California at Irvine as Professor of Chemistry and the first Chairman of the Chemistry Department. A chance conversation with an Atomic Energy Commission program officer led to Rowland being invited to an AEC-funded Chemistry-Meteorology Workshop in 1972.

There, was mentioned, Jim Lovelock’s observation of manmade chlorofluorocarbons in the atmosphere, citing the molecule as a useful tracer for air mass movements because its chemical inertness would prevent its early removal from the atmosphere. Rowland, however, realised that the molecule could not remain inert forever, and the following year he proposed a research programme, funded by the AEC, to find out what would eventually happen to the cfc compounds in the atmosphere. Working in close collaboration with postdoctoral research associate, Mario Molina, the two scientists soon realized that this was an environmental time-bomb that could destroy the ozone layer. The revelation hit the headlines in 1974 and the rest, as they say, is history. Rowland was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1978, and served on the board and as a president of American Association for the Advancement of Science 1991 to 1993 and as Foreign Secretary of the National Academy of Sciences in 1994–2002. Among other scientific and environment awards, he received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Mario Molina then at M.I.T. and Paul Crutzen of the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

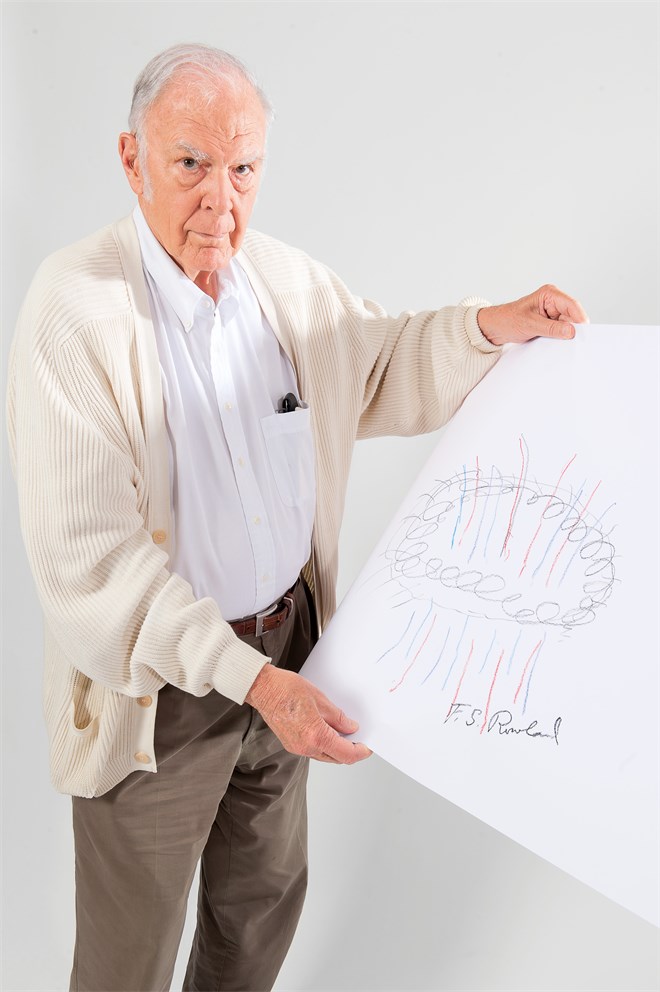

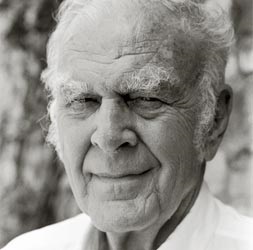

This text and the picture of the Nobel Laureate were taken from the book: "NOBELS. Nobel Laureates photographed by Peter Badge" (WILEY-VCH, 2008).

Exhibition "Sketches of Science" by Volker Steger - Locations & Dates