“We weren’t thinking, ‘This is going to win the Nobel Prize,’” said Gary B. Ruvkun of his time working as a postdoc with Walter Gilbert at Harvard University and Robert Horvitz at MIT. Together with fellow Laureate Victor Ambros, Ruvkun focused on the genes responsible for the development of a model organism, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The researchers discovered that the genes that were responsible for how fast the worm developed were lin-4 and lin-14.

Both scientists remained dedicated to the problem despite moving on to establish their own research laboratories, Ambros focusing on lin-4 and Ruvkun on lin-14. At first, Ambros and his team demonstrated that lin-4 turned off the lin-14 gene. After cloning the lin-4 gene, it was found that it produced a very short RNA molecule that didn’t encode a protein; the hypothesis was that this short molecule could inhibit lin-14 by binding to mRNA. The two groups exchanged data and discovered that the short non-coding RNA from lin-4 was complementary to the lin-14 sequence. They had found a new type of molecule that was important in gene expression, at least in C. elegans.

This was not the last word for microRNA, as it was later named. In 2000, Ruvkun published the results of his lab’s work on microRNA from another gene, let-7, which is found in many different organisms. Hundreds of microRNA have been discovered since that time, and they are fundamental to the way organisms function.

What started out as interesting work on “a slimy worm that’s only a millimetre long,” as Ruvkun called it, led to the discovery of a new mechanism for regulating gene expression.

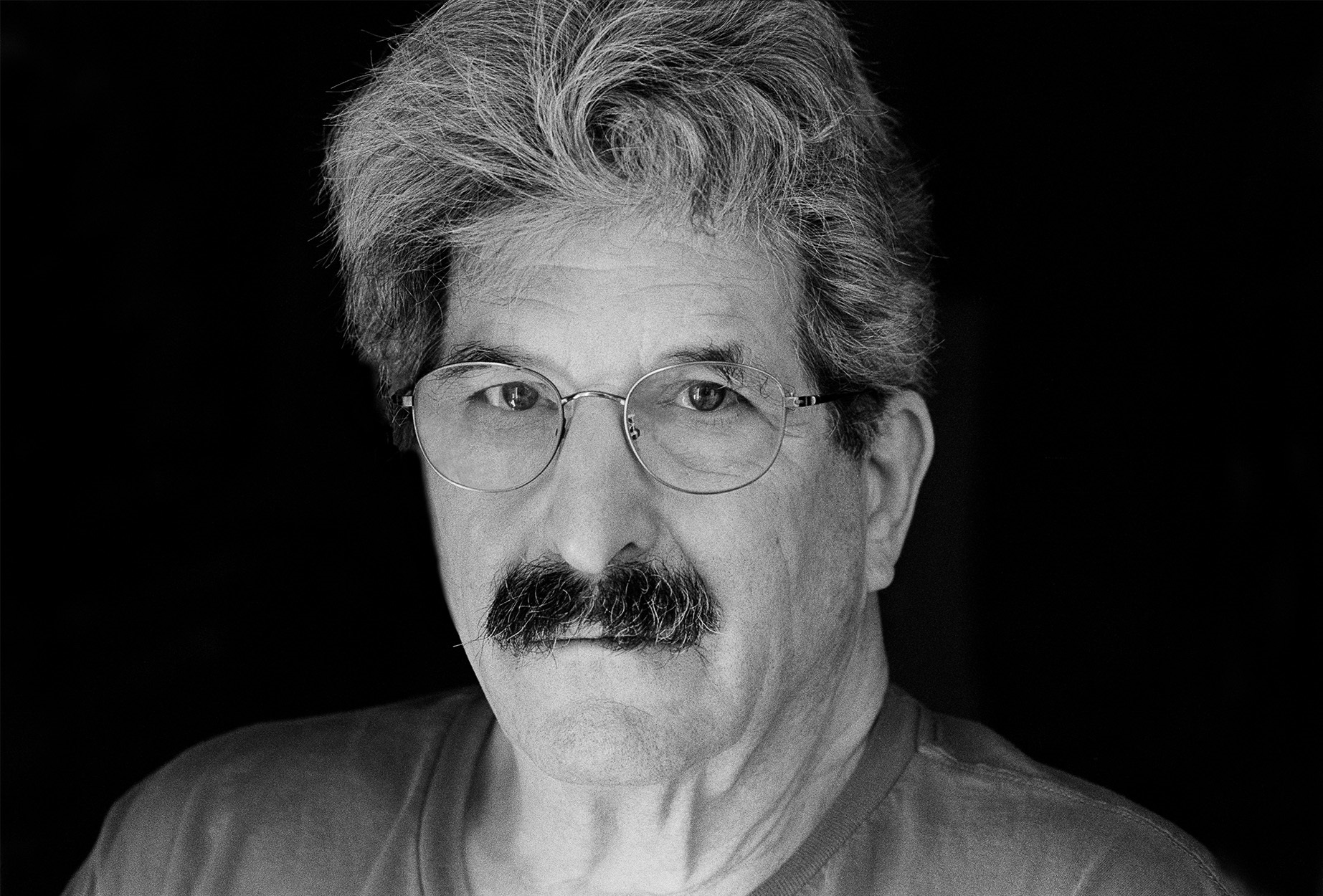

Gary Ruvkun was born in Berkeley, California on 26 March 1952. He attended the University of California at Berkeley and graduated with an A.B. in Biophysics in 1973. Ruvkun planned to go to medical school but faced several rejections. He decided to spend two years planting trees in the Pacific Northwest and travelling by bus and train through South America with a friend, before returning to graduate school. For his doctoral studies, Ruvkun studied bacterial nitrogen-fixation genes in the laboratory of Frederick M. Ausubel at Harvard University and was awarded a PhD in Biophysics in 1982. For the next three years, he was a Junior Fellow at Harvard University. Since 1985, Ruvkun has worked at Harvard Medical School, first as an assistant, then an associate professor. He is currently (2025) a Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and works at the Center for Computational and Integrative Biology at Massachusetts General Hospital. He is married to art history professor Natasha Staller and they have one daughter.