Climate Economics

By Hanna Kurlanda-Witek

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development published, “Our Common Future”, a report widely known today as the Brundtland Report, named after the Commission’s chairwoman. The report featured a definition of sustainability; “meeting the needs of the present without compromising on the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”1 In other words, how can we achieve growth, but use resources responsibly enough to make them last for the future? Economic activity affects the world’s resources, but the issue of climate change adds another dimension to the problem−is economic growth compatible with climate change? Will stepping back from fossil fuels, which we’ve relied on for growth since the Industrial Age, stabilise the climate but hinder our economic growth?

The First Approaches to Integrating Climate Change with Economics

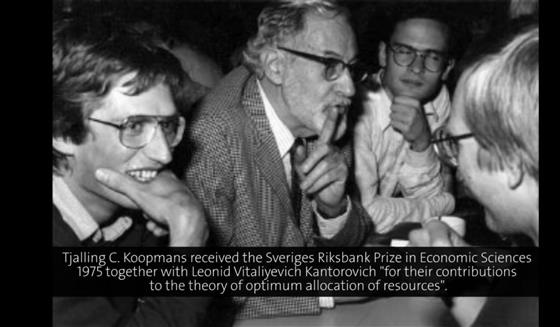

The problem is not a new one. In the 1970s, Tjalling Koopmans, who received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in 1975, supervised the Modeling Resource Group, which conducted an analysis of several energy models that calculated the demands of various energy sources in the decades to come.2 Koopmans explained the results of the study at the Lindau Meeting 1982, and he stressed the “side effects” of using fossil fuels, such as acid rain, water deterioration, and the rising CO2 content in the atmosphere. One of the models mentioned by Koopmans was the “Nordhaus energy model”:

(00:09:37 - 00:13:17)

In 1976, William D. Nordhaus published a paper titled, “Economic Growth and Climate: The Carbon Dioxide Problem.” It begins as follows: “In contemplating the future course of economic growth in the West, scientists are divided between one group crying 'wolf' and another which denies that species’ existence. One persistent concern has been that man’s economic activities would reach a scale where the global climate would be significantly altered. Unlike many of the wolf-cries, this one, in my opinion, should be taken very seriously.”3

The energy models that Koopmans spoke about in his lecture laid the foundation for the first integrated assessment model, the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy (DICE) model, authored by Nordhaus in 1992. This quantitative model analyses the economics of global warming, integrating knowledge from physics, chemistry and economics. For this work, Nordhaus received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economics in 2018. This Lindau Mini Lecture explains the three components behind Nordhaus’s model:

(00:01:13 - 00:02:23)

Dealing with Uncertainty

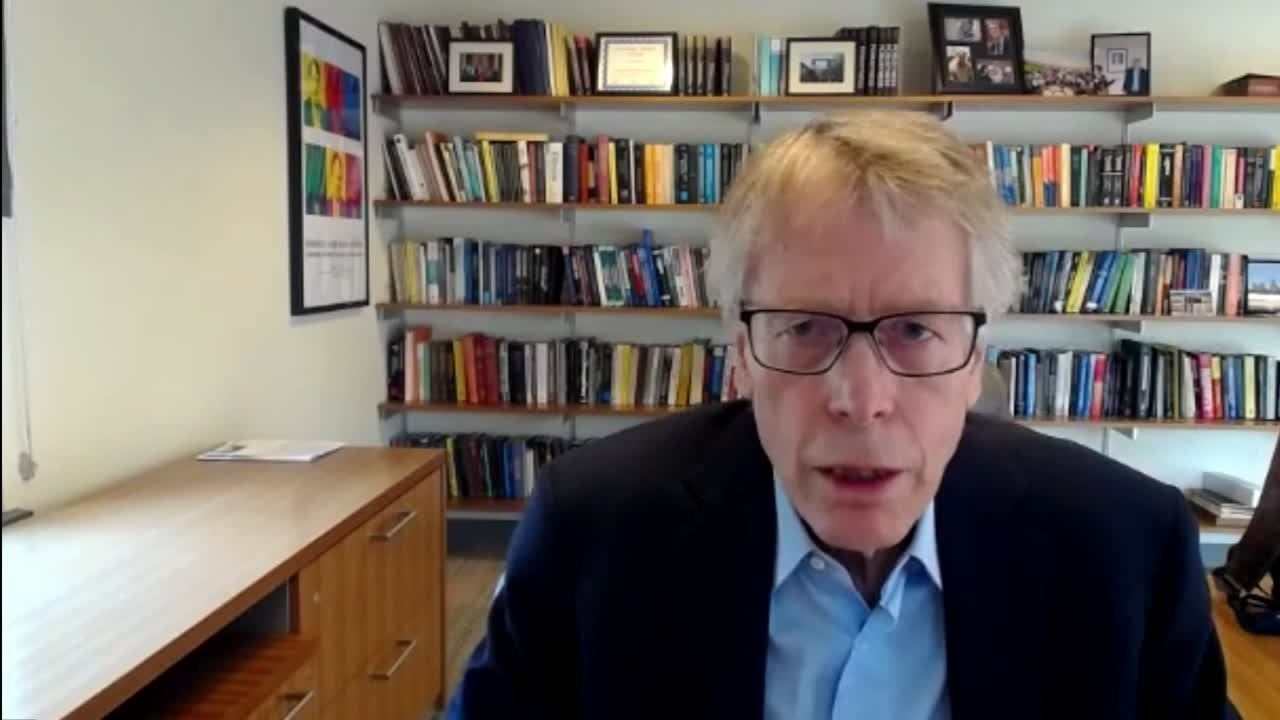

Climate change is a negative externality, a harmful occurrence that requires policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But our knowledge of the extent of the consequences is unknown and is largely based on emissions scenarios and climate change models. In his lecture, “Confronting Uncertainty in Climate Change and its Ramifications,” Laureate Lars Peter Hansen outlined the triggers behind making decisions on climate change. Should we act now or wait until we know more, and if we wait, will the outcomes prove more costly in the long term?

(00:01:35 - 00:04:07)

The current outlook on climate change is anything but optimistic. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) periodically publishes an assessment report outlining the gravity of releasing more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, and what consequences could be expected. Here, Heiner Linke, Professor at Lund University and Member of the Lindau Council, reads an excerpt of the most recent, sixth assessment report, which stipulates that an increase in average global surface temperature of 1.5-2°C will be achieved in the 21st century:

(00:00:29 - 00:02:30)

During a discussion on energy and climate at the 70th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, Robert B. Laughlin shared this sentiment, saying “We’re going to blow past 2°C.” Looking back at data from the last 30 years, since climate change became a pressing topic, the carbon budget is only expanding, while renewable energy remains a “sliver” in the data:

(00:06:02 - 00:11:30)

Putting a Price on Carbon

“If you’re going to be effective you have to raise the price, we’re going to have to get billions of people, millions of firms, thousands of governments, to take steps if we’re going to move in the direction we want, and the only way you’re going to do that effectively is increase the price of carbon.” - William D. Nordhaus, Nobel Prize lecture.

Carbon pricing is an economic tool used by governments to tax energy products. It’s a means of correcting the market failure that the emission of CO2, which is essentially free of cost, is harmful (and therefore costly) for everyone.4 Carbon pricing can be imposed with a carbon tax, which is paid by all individuals, or through cap-and-trade policies, which require governments to set a price limit (cap) on emissions in individual sectors of the economy, and to regulate trading of emission permits.5 Finland was the first country to introduce a carbon tax, in 1990, and many countries have come up with their own versions of carbon taxes and emissions trading systems since then. About 20% of global emissions are covered by either form of carbon pricing, generating over $40 billion in revenue.6

But while these tools are very useful, many scientists argue that this is not enough. Actual prices would have to be much higher to reflect the real cost of CO2 emissions. For example, airlines propose a cost of $10 per ton of carbon, but in reality, the cost should be closer to $200 per ton, which would make air travel very expensive.7

For decades, the approach was to introduce climate mitigation policies step-by-step, giving individuals and companies time for transition to a low-emission economy. Yet current forecasts demonstrate that climate change is outpacing these climate-energy policies. Many economists are proposing tougher regulations instead of add-on costs that are invisible to those who can afford them and are an added burden to low-income individuals, who aren’t able to change their preferences.8

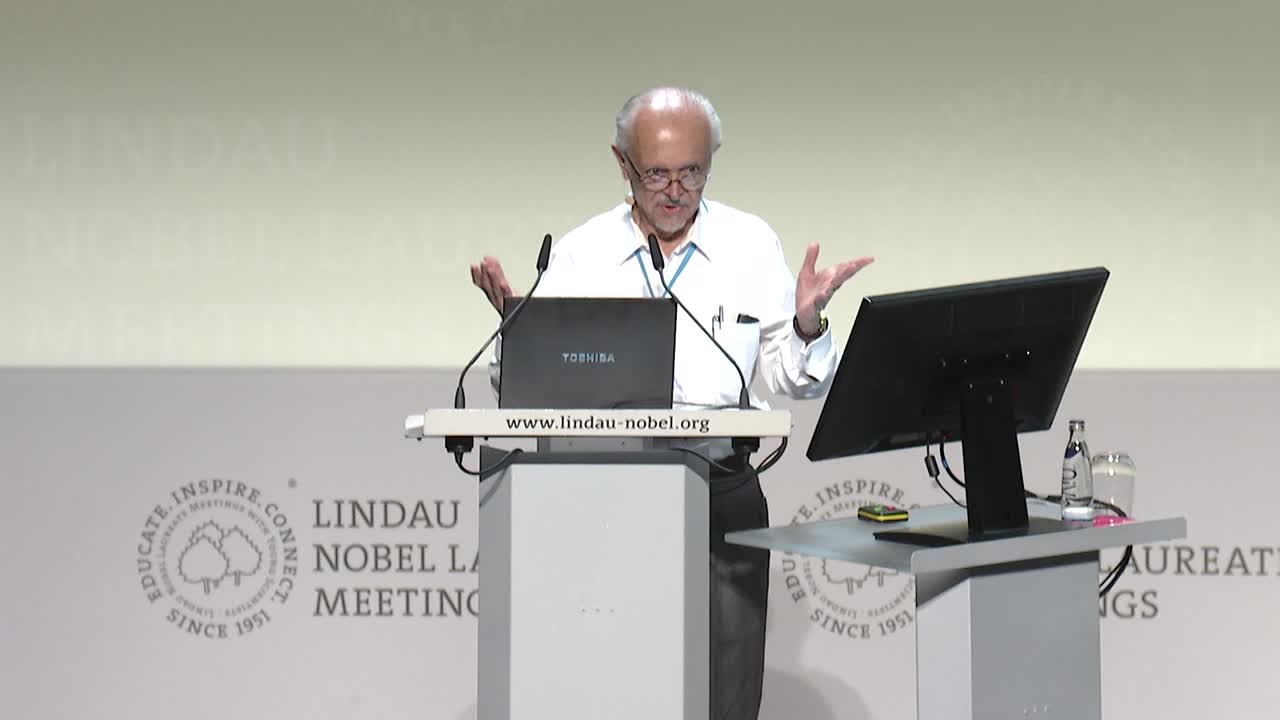

In an editorial for the European Economic Review, economists Cameron Hepburn, Lord Nicholas Stern and Laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz postulated that pricing carbon is an insufficient measure at a time of urgent need for widespread structural changes, for example in infrastructure, the design of cities, and industrial supply chains. As the late chemist Mario J. Molina stated during his last lecture in Lindau in 2017, there’s no silver bullet in solving the climate change problem. He also cited key findings from the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, a report written for the UK government in 2006 by Lord Nicholas Stern. Will cutting the amount of greenhouse gases emitted to the atmosphere cost us too much? And what will the financial damage be if we don’t act?

(00:20:03 - 00:25:37)

Climate Action Through Policy

Cost benefit analysis (CBA) has long been the conventional method of deciding on government policies on climate change. If costs are higher than benefits, the policy proposal is abandoned, but if benefits are higher, the policy can be implemented. Costs are associated with abatement approaches, such as increased energy efficiency of particular sectors or individual companies, waste reduction, reforestation, and green business building. However, CBA is viewed by many economists as inadequate for the current policy changes required to slow climate change, as it underestimates the potential scale of problems resulting from climate change.9 There are many factors that should be considered other than economic scenarios; the quantification of environmental aspects, such as species preservation, the impact of the physical environment, societal damage, and the costs of decarbonisation, to name just a few.10

Some economists, such as Stiglitz, favour cost effectiveness analyses, where climate change policy is built around a particular target, for example 2°C of warming by the end of this century, with policies then put in place to reach this target as inexpensively as possible.11 Risk-opportunity analysis is also touted as a better alternative to CBA, as it may address the factors of widespread transformational change needed to alleviate climate change, accelerating more challenging climate change policies.12 This economic analysis integrates dynamics, heterogeneity and uncertainty into the decision-making process, and as such may be more suitable in characterising structural, non-marginal change.13

During his lecture, Lars Peter Hansen presented an example of a model showing how uncertainty can be incorporated into climate policy using dynamic decision theory:

(00:15:32 - 00:19:19)

Maintaining Focus

2022 has been particularly rife with uncertainty, bringing war, and a food and energy crisis into the spotlight. Governments have scrambled to stock up on fossil fuel resources ahead of winter, provoking the sentiment that climate change has been moved to the sidelines as more pressing issues have taken priority. “As inflation bites and living standards are squeezed, firefighting at home has distracted governments from the fiercer blaze on the horizon,” was how one recent article in the Financial Times aptly compared the situation.14

But there are some indications that this turbulent period can make way for a faster roll-out of renewable energy in the long term. In March 2022, the European Commission presented the REPowerEU Plan15, an ambitious project to end the EU’s reliance on fossil fuels from Russia; the EU’s main supplier of crude oil, natural gas and solid fossil fuels.16

If adopted by the European Parliament, the plan will be partly funded by carbon market revenue, the EU Innovation Fund, which is currently used for breakthrough green technologies, and from the early sale of carbon permits, which would leave a fewer number of permits to be used by 2030, pressing member states to use alternative energy sources.17

Recently, India, the world’s third-largest CO2 emitter, has proposed a national carbon market, which is a first step in tackling the country’s dependence on coal as an energy source. Establishing the market will help devise ways to reduce emissions for each carbon-intensive sector, as well as create an emissions inventory to identify particular sources of CO2.18

The COP27 climate summit in Egypt in November 2022 focuses not only on areas that dominate at every climate summit−decarbonisation and climate adaptation, but also on the global food system and building strategies for growing food in a climate-resilient way.19 The pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and extreme drought events have caused food shortages in some developing countries.20

High-income countries are able to sustain billion-dollar agricultural production, but at the expense of another precious resource−water. In this lecture, economist Paul R. Milgrom explained how despite severe drought in California, there are vast differences in the marginal value of water, pointing to market failure:

(00:00:56 - 00:04:49)

With high inflation in many countries and the possibility of an economic downturn, some politicians and economists propose waiting out the turbulent period before implementing climate change policies. A World Economic Outlook report has specified that a gradual increase of budget-neutral policies, such as carbon taxes, in order to achieve a 25% reduction in emissions by 2030 would cost countries very little: 0.15-0.25% of global economic growth, and a rise in inflation by 0.1-0.4%. Delaying the transition will cause higher inflation and a decrease in GDP by 1.5% over a four-year period.21

The argument that the economy will slow down if we encourage decarbonisation is always on the table. But the strategy should be to decouple economic growth from CO2 emissions using climate policies, investment in low-carbon energy and technological development.22

Technology Requirements for a Cooler Climate

“If necessity is the mother of all inventions, we’ve got the mother of all necessities in climate change,” said Nobel Laureate Steven Chu. Without new technology and breakthroughs in innovation research it’s hard to imagine a transition to a low-carbon economy.

In this lecture fragment, Nobel Laureate Carlo Rubbia explains that the key to sustainability is to develop new technologies:

(00:08:35 - 00:09:27)

One of the problems of expanding investments in low-carbon innovation is that companies often decline to invest in a new technology for a small existing market.23 Also, no matter how good the new technology is, it won’t be adopted by individuals, companies, or communities until it becomes inexpensive, or at least comparable in cost to the currently used technology. This was explained by Steven Chu in the short educational video, “Fuelling Controversy”:

(00:08:32 - 00:09:01)

Until the technology becomes an economically viable alternative, government subsidies are usually what provide the incentive to make the technology widely available. This is an example of how climate policy and technology go hand in hand, and they will become even more integrated with the advancement of artificial intelligence, machine learning and the proliferation of smart devices; issues concerning data use and storage will have to be safeguarded by appropriate policies.

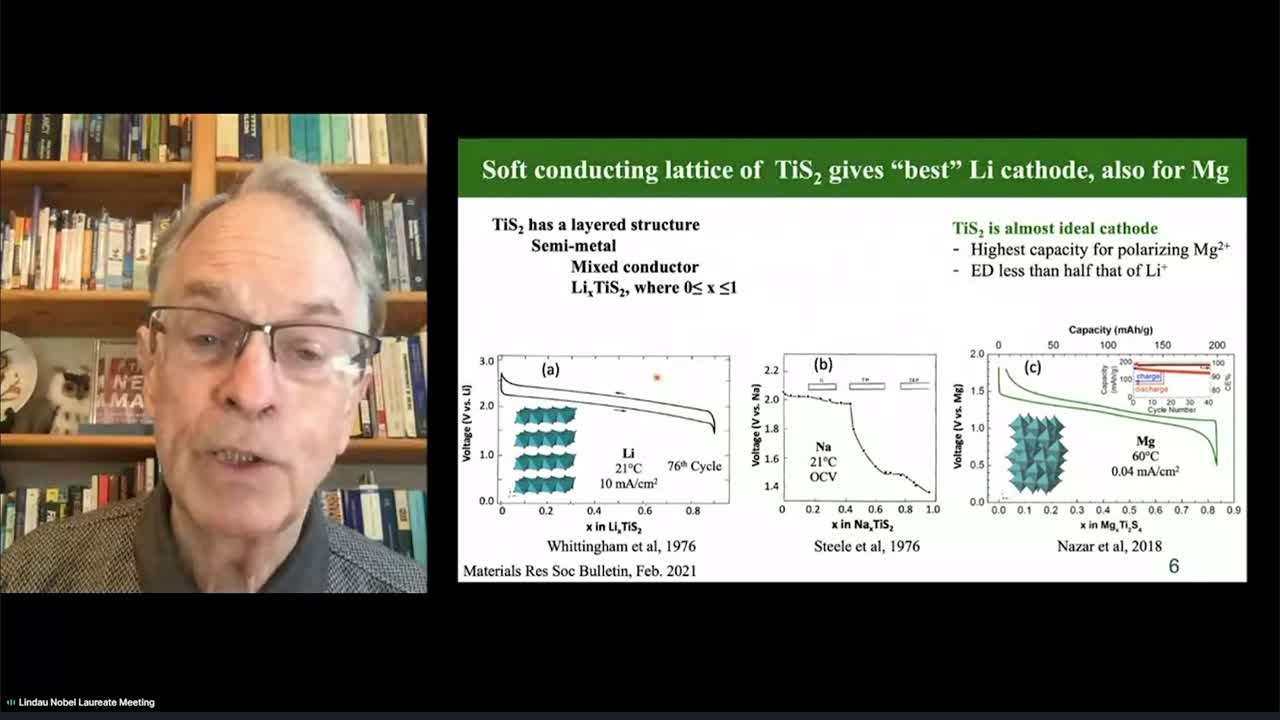

In this lecture fragment, Nobel Laureate M. Stanley Whittingham gave examples of how positive changes in existing technologies, manufacturing processes and policies don’t have to be overly costly or complicated:

(00:36:25 - 00:38:11)

Economy Driving Social Change

Climate change forecasts may be grave, but that doesn’t affect the preferences of most people. Individuals live in the here and now and it’s very difficult to convince them to change their behaviour for the sake of future generations. As explained here by Nobel Laureate Brian P. Schmidt, economics will have the last word on the choices that we make.

(01:21:10 - 01:22:01)

I would like to conclude this topic cluster with four points on how to combat climate change, presented by William Nordhaus during his Nobel Prize lecture in 2018. These points succinctly yet thoroughly show how the effects of climate change should be mitigated through a blend of science, policy and economics:

1) accept and understand the gravity of climate change, scientists must continue their research and citizens must reject politicians who spread false and tendentious reasoning,

2) we must establish policies that raise the price of CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions,

3) we must act locally and nationally but also at a global level,

4) we need rapid technological change in the energy sector.

Footnotes:

[1] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

[2] https://www.nber.org/reporter/2017number3/integrated-assessment-models-climate-change

[8] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/business/economy/economy-climate-change.html

[13] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378021001382#b0360

[14] https://www.ft.com/content/6f352052-f2bc-401a-beed-b89d9e98a23d

[15] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3131

[19] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/cop27-why-it-matters-and-5-key-areas-for-action/

[20] https://www.ft.com/content/6f352052-f2bc-401a-beed-b89d9e98a23d

[23] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166497222001596